Mission or Money? The Quiet Boom of CICs and the Questions No One’s Asking

Over the past decade—but especially in the last few years—the UK has seen a sharp rise in Community Interest Companies (CICs). Originally conceived as a hybrid model to blend social purpose with commercial discipline, CICs were designed to sit neatly between charities and traditional limited companies. Today, they are one of the fastest-growing business structures in the country.

Supporters call this a success story: proof that British enterprise is becoming more ethical, more community-focused, and more innovative. Critics, however, see something else entirely—a business model increasingly stretched to its limits, and perhaps beyond its original intent.

So what’s really driving the CIC boom? And is it still about community interest—or something more convenient?

A Model Built on Trust

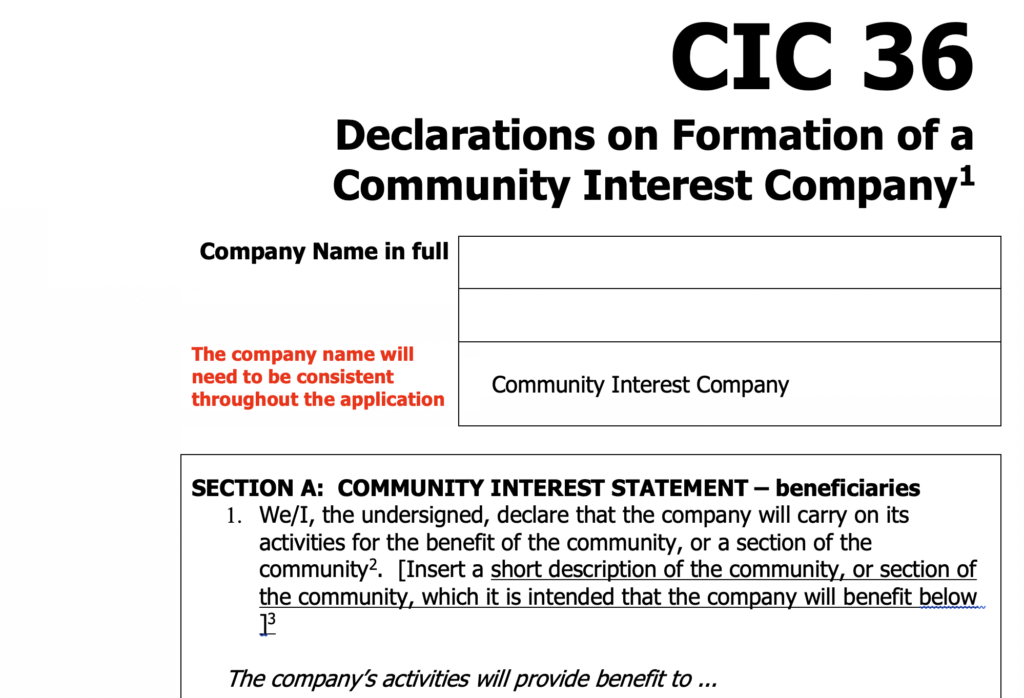

CICs were introduced in 2005 to solve a real problem. Many socially minded founders wanted to trade commercially but struggled to fit within the rigid frameworks of charities or standard companies. CICs promised flexibility with accountability: profits could be made, but assets and dividends would be capped, ensuring the “community interest” remained front and centre.

At least, that was the theory.

In practice, CICs enjoy a powerful combination of credibility and freedom. They are regulated—but lightly. They can pay staff, generate revenue, and contract like any business, while benefiting from public trust traditionally reserved for charities. For funders, councils, and corporate partners, the CIC label often signals legitimacy and social value before a single balance sheet is reviewed.

That trust is increasingly valuable.

Why CICs Are Everywhere Now

The recent surge in CIC formations isn’t happening in a vacuum. Several overlapping pressures have made the model unusually attractive.

First, public funding has become more competitive and more conditional. Grants increasingly favour organisations that demonstrate “social impact” while remaining financially sustainable. CICs tick both boxes neatly.

Second, the rise of ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) priorities has reshaped procurement. Corporates are under pressure to work with “purpose-led” suppliers, and CICs offer an easy win—especially compared to the complexity of partnering with charities.

Third, the startup ecosystem itself has changed. Founders are more comfortable blending mission and margin, and younger entrepreneurs often see social purpose as a branding advantage as much as a moral one.

None of this is inherently problematic. But it does raise an uncomfortable question: are CICs being chosen because they are the best structure for community impact—or because they are the most useful structure for winning work?

Blurred Lines and Soft Oversight

At the heart of the controversy is regulation—or the perceived lack of it.

CICs are overseen by the Office of the Regulator of Community Interest Companies, but enforcement is widely seen as reactive rather than proactive. Annual community interest statements are required, yet critics argue these can be vague, unchallenged, and difficult for the public to interpret.

Unlike charities, CICs are not subject to the same depth of scrutiny. Unlike standard companies, they trade on moral capital. This leaves them occupying a grey area where intentions matter more than outcomes—and where poor actors can hide in plain sight.

There is growing concern that some CICs operate little differently from conventional businesses, except in how they market themselves. High executive pay, opaque subcontracting, and limited demonstrable community benefit have all been flagged by sector insiders, though rarely challenged publicly.

The result? A model that relies heavily on good faith in a marketplace that increasingly rewards optics.

The Risk to the Sector

Ironically, the biggest risk posed by questionable CIC practices is not regulatory—it’s reputational.

As more CICs enter the market, competition for funding, contracts, and attention intensifies. Those doing genuine, difficult, community-rooted work now find themselves competing with organisations that are slicker, better resourced, and sometimes less accountable.

If funders and partners begin to lose confidence in the CIC badge, the fallout will not be evenly distributed. Smaller, grassroots organisations—often the very groups CICs were meant to empower—will feel it first.

There is also a policy risk. If CICs are increasingly perceived as vehicles for “mission washing,” political appetite for reform will grow. That could mean tighter caps, heavier reporting requirements, or reduced flexibility—changes that would fundamentally alter the model.

A Model at a Crossroads

None of this means CICs have failed. On the contrary, many deliver real, measurable social impact and operate with integrity in challenging environments. The issue is not the existence of CICs, but their unchecked proliferation without a parallel evolution in oversight and transparency.

The UK now faces a choice. CICs can either mature into a robust, trusted pillar of the social economy—or drift into a catch-all structure whose meaning is diluted by overuse.

For founders, funders, and regulators alike, the question is no longer whether CICs are growing. It’s whether growth without sharper accountability ultimately serves the communities they claim to exist for.

Because when “community interest” becomes a competitive advantage rather than a binding commitment, trust—once lost—is hard to rebuild.

“In 2023–24, more Community Interest Companies were registered than new charities in the UK — proof that ‘social impact’ is increasingly being chased as a business model, not a charity mission.”

Inspire2Aspire (2025) Community Interest Companies (CIC). Available at: https://inspire2aspire.co.uk/third-public-sector/community-interest-companies-cic

No Comments